Walking and thinking; ancestors.

Homo Sapiens are by definition vertical and bipedal. As a species we have evolved to move slowly, consistently and in a sustained manner over the surface of the planet — and as we move we observe, we map, we remember and we think.

Thanks to the hundreds of thousands of years that our hominid ancestors have paced the earth the act of walking now takes very little of our mental capacity — it has, in contemporary terms, a low cognitive overhead — walking places scant demand on our attention, which in turn liberates our minds to engage in creative and speculative thought.

Surprisingly the equally pleasant occupation of, for example, small boat sailing functions in stark contrast, in that it demands a high and constant level of attention. To sail on the open sea is to be totally absorbed with the nuances of balance and the forces of wind and water, calculating trim and helm. The mind is fully occupied and enters into an oblivion where philosophy is banished by a focus upon the ever changing moment.

In this respect walking is unique. We have evolved to function at walking pace and all other velocities tend to distort and disturb our perceptual, cognitive and imaginative thought processes. At walking pace conversation is possible as it syncopates with the rhythmic cadence of the step and the lungs (whereas running renders conversation difficult or impossible). Moreover solitary walking offers the very special gift of imaginative reflection and there are several convincing reasons for this.

One could be forgiven for assuming that the optimal situation for thinking is to sit quietly in focused meditation but the efficacy of the sedentary state has time and again been contradicted by prominent thinkers throughout history. Henry David Thoreau reflected on the direct connection between walking and thinking.

Methinks that the moment that my legs begin to move my thoughts begin to flow.

There is nothing magical in this process, walking immediately increases the blood flow and thus supplies additional oxygen to the brain, which, when so exercised on a regular basis has been demonstrated to stimulate additional neural connections, generating fresh neurones, increasing the capacity for attention and memory.

Attention is a limited (but thankfully renewable) resource, however it gradually diminishes over the course of the day. Again, it has been well demonstrated that prolonged periods of sedentary work (which is sadly the norm for a large percentage of contemporary labour) is physically and psychologically damaging, diminishing the level of attentiveness, imaginative thought and memory. Even standing at a computer terminal is now widely recognised as beneficial as it remedies many posture related issues of sedentary work, but importantly standing also engages the hormone regulating endocrine system (parts of which shut down whist seated).

Walking and thinking; a cultural orientation.

If you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled your affairs,and are a free man; then you are ready for a walk.

Thoreau explains that in the middle ages vagabonds would use the pretence of a pilgrimage to the crusades to ask for alms, claiming to be walking à la Sainte Terre – giving us the word saunter for an aimless walk undertaken by idlers. By the nineteenth century sauntering had developed into a fashionable middle class pastime — epitomised by the Flâneur, the “passionate spectator” of Charles Baudelaire who roamed the Paris boulevards taking in the endless urban parade.

poets find the refuse of society on their street and derive their heroic subject from this very refuse. This means that a common type is, as it were, superimposed upon their illustrious type. … Ragpicker or poet — the refuse concerns both.

01. From the Louis Huart, Physiologie du flâneur, Aubert et Cie 1841.

However to walk without explicit purpose and time constraints is perhaps one of the most productive and creatively liberating things we can do; and Baudelaire made an even more precipitous suggestion in the fifth stanza ofhis poem Le Voyage in the 1857 publication of Fleurs du Mal. His vrais voyageurs (or real travellers) foreshadow the spirit of the Dérive, a practice much vaunted by the Situationist Internationale in the mid twentieth century — in effect a pedestrian free-fall into fate.

Mais les vrais voyageurs sont ceux-là seuls qui partent pour partir;

coeurs légers, semblables aux ballons, de leur fatalité

jamais ils ne s’écartent, et, sans savoir pourquoi, disent toujours: Allons!

But real travellers are those who just leave for the sake of leaving,

Hearts as light as balloons, never avoiding their destiny,

And without knowing why, they always say: “Let’s go!”

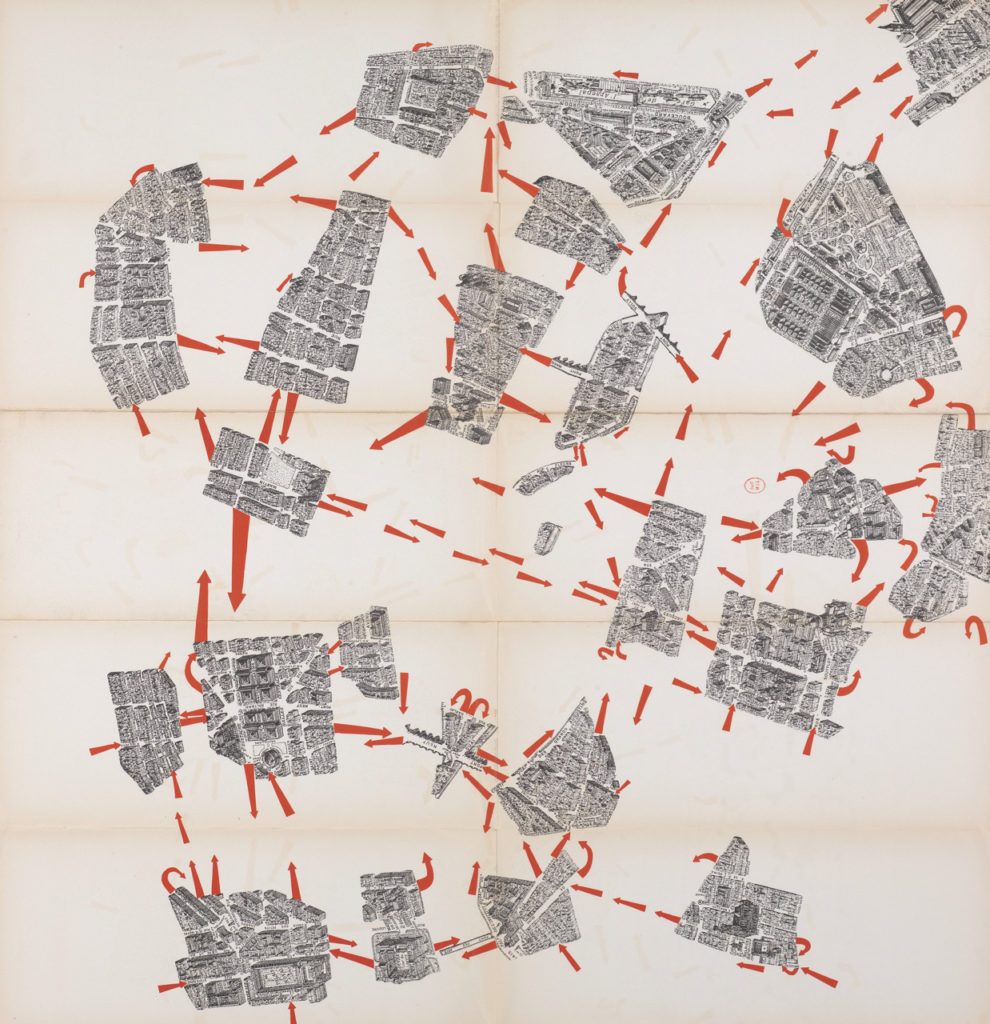

In1955Guy Debord, the principal protagonist of the Situationist International, characterised psycho-geography as — the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals – An informed and aware wandering, with continuous observation, through varied environments. It can be sought and can lead anywhere.

In effect this is the Flâneur turned forensic and with a modus operandi synonymous with the tools of the trade of the writer and the poet — acute observation and a prodigious capacity to recall events in-situ.

02. Guy Debord, Guide psychogéographique de Paris : discours sur les passions de l’amour, International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus 1957.

Psycho-geography has since entered into the literary sphere as the geospatial mappings of the literary imagination, manifest, for instance as physical tours which re-enact the trajectories of novels — the day’s meanderings of Leopold Bloom around Dublin in James Joyce’s Ulysses — or pastoral walking tours of the imaginative hinterland of the Brontes — a retro-fitting of the literary imagination.

Walking and thinking; some beginnings.

However the well-spring for this fusion of creative thought and walking can be sourced from an earlier time — the English Romantic poets, in particular William Wordsworth and his siter Dorothy.

Wordsworth, his diarist and poet sister Dorothy, and frequent companion and close friend Coleridge, were indeed remarkable in going against the grain and following their passion for arduous, long distant walks, in the often unforgiving Northern English terrain. At the time, travelling by foot on the public highways and roads was a risky business, as they were peopled by paupers, vagabonds and footpads: only those who were forced by circumstance or trade would walk. In other words, the public highway was a contested and dangerous place. The wealthy restricted themselves to promenades in manicured gardens or leafy urban boulevards, where the purpose was to see and be seen rather than to commune with nature.

Wordsworth, in his coupling of the creative process with outdoor walking, is often credited as having initiated the English Romantic tradition; he has been described by the American author Christopher Morley as ‘one of the first to use his legs in the service of philosophy.’ The Wordsworths influenced one another: Dorothy provided material for a famous Wordsworth poem when she wrote in her journal in 1802:

I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about & about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing.

The Wordsworths’ extensive walks developed into extended expeditions all over Europe, encapsulating the Romantic tradition: walking in the service of the imagination and finding the sublime in nature.

In 1792, during his second trip to revolutionary France, William Wordsworth met an extraordinary countryman by the name of John ‘Walking’ Stewart. Stewart had spent thirty years walking throughout India, the Middle East, parts of Africa, Europe and the North American colonies, and had come to the attention of the public through his two publications The Apocalypse of Nature (1791) and Travels over the most interesting parts of the Globe (1792). These works espoused his own brand of materialist philosophy, based on his direct experience of the physical and cultural landscapes through which he had journeyed.

In the volatile atmosphere of revolutionary Paris, it is highly probable that the twenty- two-year-old Wordsworth was strongly influenced by Stewart, both by his depth of experience and by the dedication to the practice of walking as a source of knowledge and inspiration. Stewart may well have provided the impetus and the confidence to launch Wordsworth into the landscape. Shortly afterwards, Wordsworth’s first volumes of poetry An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches were published (1793).

Wordsworth fused a rigorous physical walking regime with the engine of his creative practice. In his lifetime he walked some 175,000 miles; if we estimate a generous 3 and a half miles per hour, we can calculate some 50,000 hours of reflection, much of which found its way into his poetry. His work resonates with subsequent generations of visual artists, notably the generation of painters that immediately followed. These were the Romantic painters who shared his subjective vision of the sublime in nature: Caspar David Friedrich, J.M. Turner and John Martin.

Wordsworth’s practice of pastoral walking continues to resurface in contemporary culture, almost as if his legacy has given permission for the visual arts to embrace nature and landscape as a subject. The pursuit of walking in landscape re-emerged in the 1960’s conjunction of conceptual art, landart and systems art. In the English context, where ‘rambling’ had been something of a national pastime since the mid-nineteenth century, the de-materialisation of sculpture was manifest in the work of several artists, who began to devise long distance walks. These walks were mostly undertaken solo, in which the walk itself was the programme (or conceptual activity). Byproducts of the walk could include ephemeral stone arrangements (produced enroute), documentary photographs, and text works; post-produced in exhibitable or publishable forms.

At first appearance, the work of the British ‘walking’ artists such as Richard Long and Hamish Fulton may appear quite at odds, in their strict conceptualist formulation, with the subjective tableaux of Turner and Martin that foreground the sublime. However at heart they are driven by a similar programme of direct contact with nature which embraces physical endurance, hardship, and often solitude.

Both Long and Fulton came through the experimental sculpture course at Central St. Martin’s School of Art in London in the 1960’s under the tutelage of Peter Atkins.

During this period sculpture was at a cross-roads, dematerialising and engaging in conceptual and linguistic structures; in the case of both artists, this evolved into relatively simple task-based conceptual programmes, with walking in the landscape as the core.

Unlike the American ‘LandArt’ movement, which used landscape as a location and physical material source to create large terra-formed sculptural works (generally funded and on-sold by galleries) the English walkers travelled light. The conceptual programme was often little more than a set of map co-ordinates (walking from John O’Groats to Lands End for example) with perhaps the creation of an ephemeral sculptural arrangement along the way — or writing short textual descriptions to accompany documentary photographs. These were not so much performative works as direct personal experiences of the landscape; in fact the walks were not claimed as art per se but as events that engendered art — manifest as evidence, or reinterpreted in a gallery at a later date.

Richard Long’s work A Line Made by Walking of 1967 was an early instance of walking art. A black and white photograph revealed a long path through grass made by Long’s feet. As Rebecca Solnit has observed, the work, despite it earthiness, contained an ambiguity: was the work of art the performance of walking, or the line made by walking, or the photograph of this natural sculptural form, or all of these? From that point, ‘walking became Long’s medium.’

It is ironic that although Long and Fulton appear to have initially eschewed the commercial gallery scene, heading off for the hills to create art, they have both enjoyed considerable public acclaim. Despite their insistence on a practice that would appear dematerialised in a sculptural sense, both maintain a consistent output of lightly physical works: Long’s mud-smeared walls and floor-based stone arrangements; Fulton’s landscape photographs and cryptic texts. More recently, Fulton has made rigorously designed public communal walks that play with the ratios of time and distance, and which he orchetrates and views as sculptural objects. These are in effect highly structured conceptually-based group walking systems — as art experiences.

One eccentric addition to the ‘walkers’ is the gardener and poet — Ian Hamilton Findlay. Rather than traversing the terrain, Findlay has remained firmly rooted in the soil of ‘StonyBrook’, the artist’s garden in Dumfrieshire, Scotland that he developed over several decades. Findlay combined landscape design, concrete poetry and an acute knowledge of history to form a living artwork which the visitor ‘performs’ — by walking the labyrinthine paths of the StonyBrook gardens, ponds and heathlands.

In the commercial frenzy centred on the YBA (Young British Artists), the landart movement produced a poster-boy in the guise of Andy Goldsworthy. He is of note for his delicate arrangements of leaves, ice crystals and other ephemera, situated before the camera in exotic, pristine expedition environments. Goldworthy’s extremely popular, well-publicised practice is also programmatic, but in the cool commercialisation of the sensibility pioneered by Long, Fulton and Findlay; here ephemeral art becomes a sediment in oversized coffee-table publications.

Walking and thinking; memory and loci.

In “The Art of Memory” 1964 Frances Yates paints a vivid picture of the antique technique that enabled Orators to place memory objects, such as lengthy quotations, within the labyrinthine spaces of classical architecture. By visualising an architectural interior, real or imaginary, a speaker might place here a red cloak over a sculpture and there, a sword on a table, each act of placement serving as a mnemonic trigger to locate a passage of Rhetoric. By memorising a stroll through this virtual architecture the Orator could re-enact his steps and thus retrieve a vast amount of correctly sequenced material.

The capacity to associate thought and more specifically memory, be it a classical argument or the entire cultural history of a tribal group, with a geo-spatial location is frequently overlooked or under-rated. Ironically it may well be that this form of situated knowledge is not only vital to human society but is also fundamental to many non-human species, being vital to navigation, and the successful location of breeding sites for migratory species.

For humans, this is a deep-seated evolutionary feature that embodies thought as action in the physical environment. Thought and memory are therefore not abstracted and deracinated, but are complex products that link memory and cultural knowledge with specific places and to the many sensory attributes of such loci, their odours, visual markers and acoustic properties, which subsequently serve as powerful associative triggers.

These expanded sensory inputs that walking provides (especially in natural environments) afford different modalities of thinking that are in stark contrast to those based upon extant knowledge, contained in books and which support the assumptions of the status quo. Nietzsche was quite clear about his preferences then it came to thinking.

We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors — walking, leaping, climbing, dancing preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea where even the trails become thoughtful.

Nietzsche who thought and wrote whilst on the move was explicit about his method.

Only ideas won by walking have any value.

Walking and thinking; augmented reality.

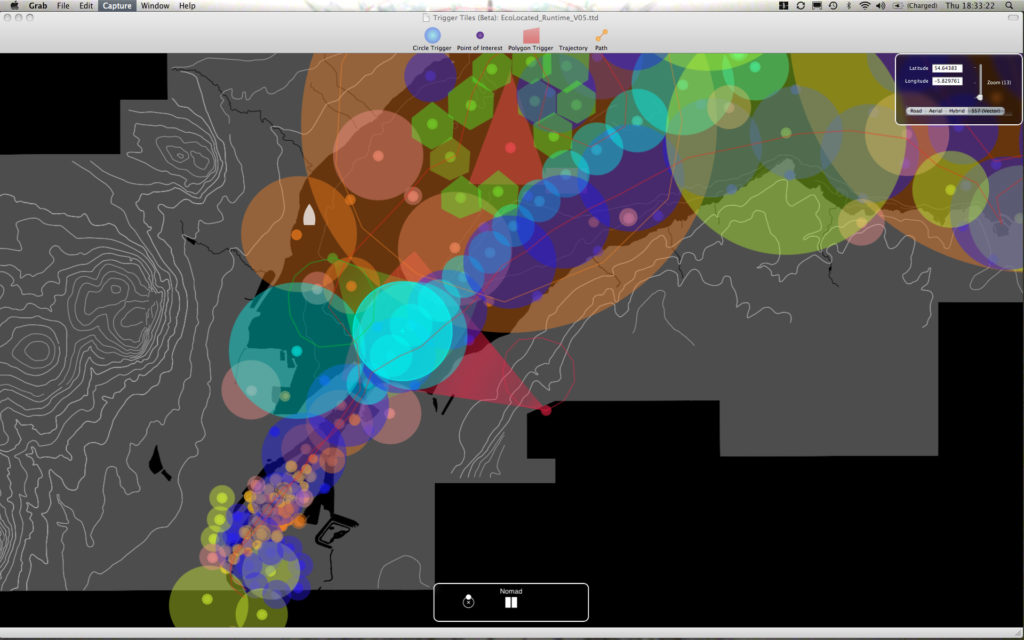

It is a series of short conceptual steps from the mnemonic techniques of the classical orators, or Nietzche’s insistence on thought gestated by walking, to a contemporary creative practice that employs the digital technologies of augmented reality to seed the terrain with thoughts, images, sounds and memories. Artworks that employwalking as a spatial foundation for thought and the establishment of memory are demonstrated in a prequel to the author’s current research which took up the conceptual model of the Ars Memoriae but transposed it into the realm of digital technology. From 1997 to 2006 the author developed a series of collaborative cross-disciplinary art and science projects working with the concept of GPS-driven, location based audio cartographies designed to deliver an experience of a virtual audio world overlaid upon the landscape. Whilst such works share a common conceptual lineage with earlier examples of Land-Art they manifest in a radically different aesthetic form, inviting participants to ‘perform’ and literally ‘compose’ location sensitive experiences through the act of walking. In effect no two individual experiences could be identical which raises the question of where meaning and creative control resides — in the efforts of the author or the experience of the participant?

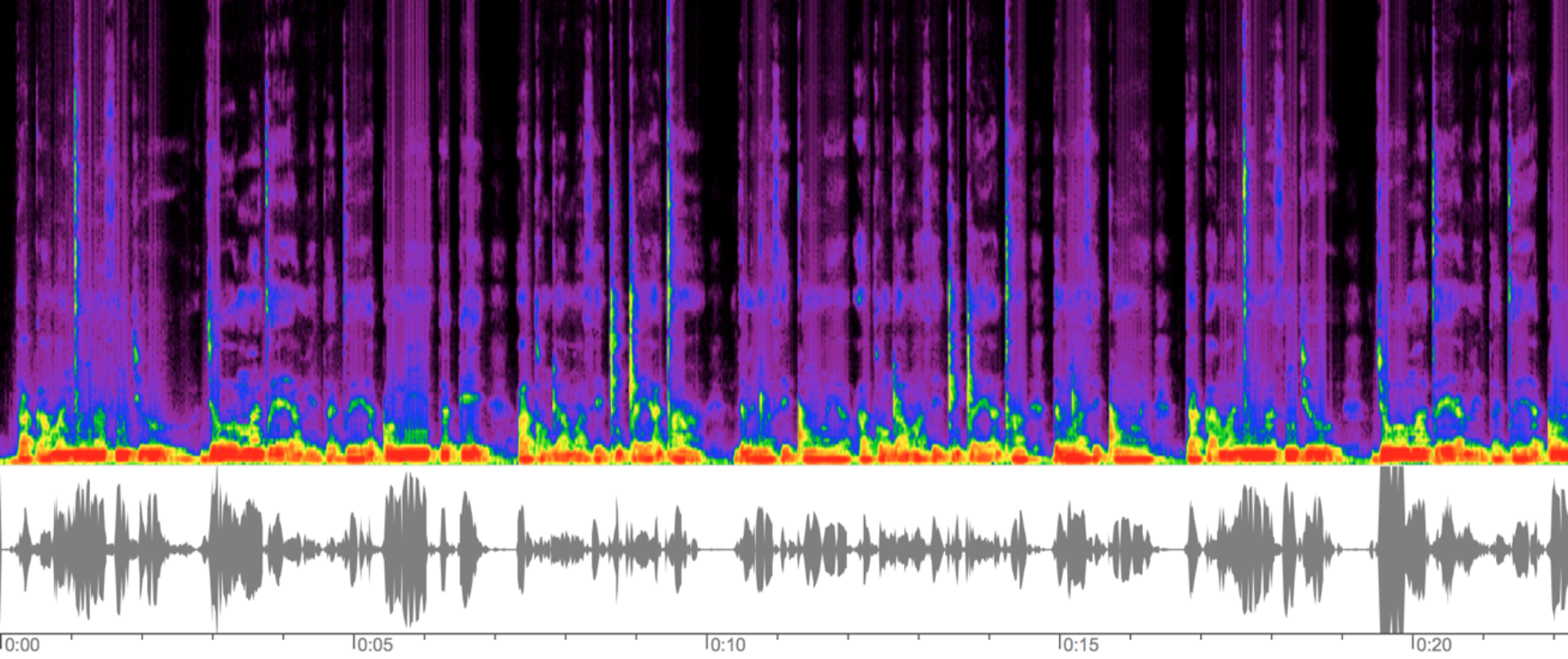

Two major project teams, SonicLandscapes (1998 ~ 2001) and AudioNomad (2003 ~ 2010) transposed the imaginary architectural metaphor of the Ars Memoriae into the cartographic space of digital maps, (themselves functioning as a representation of the physical location of each project). The software delivered a Sonic-Landscape, by assigning sound files, trajectories, and other acoustic properties and parameters to multiple locations within this virtual domain ready to be triggered by the GPS position and trajectory of a mobile listener.

Whereas the classical rhetorician would recall a walk through an imaginary architecture in order to retrieve the sequential elements of a speech, the participants in a SonicLandscapes or AudioNomad project could literally walk in a real environment. The walkers position and orientation data would drive a multi-channel soundscape, which software would delivered to them via surround-enabled headphones. In this manner the soundscape would appear to emanate from the surrounding landscape and its objects.

Users experienced an uncanny parallel audio world in which (virtual) aural memories of particular sites were superimposed over contemporary audio reality.

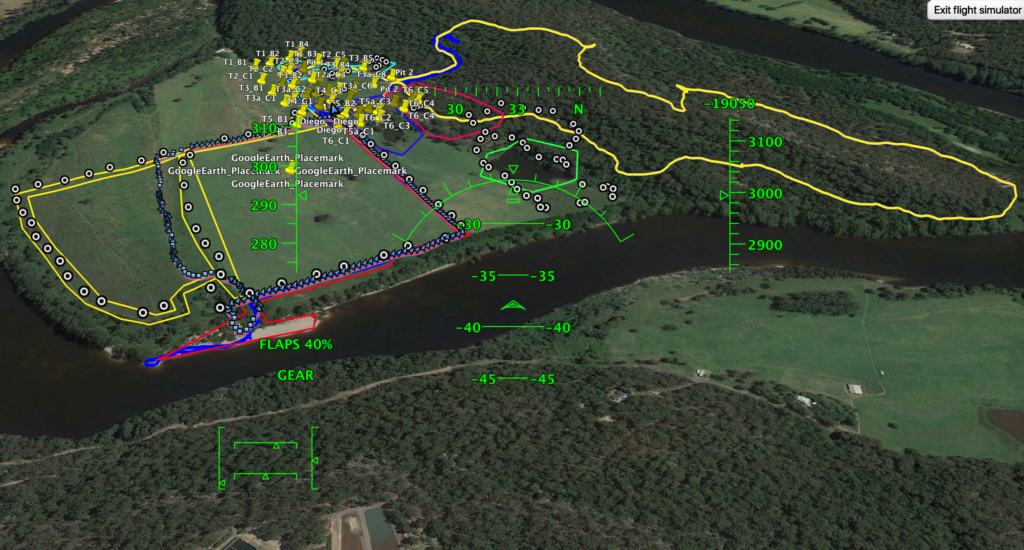

03. AudioNomad screenshot of spatial audio editing screen for the Ecolocated project – Belfast Lough, 2009.

Alternative developments departed from the basic mode of walking as the interactive soundscape was deployed to massive surround-speaker arrays mounted within large mobile platforms, as in the case of the ship-mounted works Syren for ISEA2004 in the Baltic Sea and Syren for Port Jackson 2006 on Sydney Harbour in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Art. Here the listener still moved through the landscape/seascape but as one transported both literally and metaphorically, on a ship. In a subsequent development for museum exhibitions, the system was configured to be driven from a console mounted interactive map allowing the user to navigate a virtual mapped space and simultaneously drive a powerful, immersive, surround speaker array.

Back to Earth.

Ironically the creative foundation for these sophisticated augmented audio reality works was always firmly rooted on the ground. For each project the audio content was painstakingly collected during hundreds of hours of field recording, amassing environmental and urban soundscapes as well as vocal and musical material. This is where the location of ‘location-sensitive’ really comes from — a gradually developed intimate knowledge formed by a process of deep listening to an environment, not to mention equally lengthy durations spent in the studio editing and designing the soundscapes..

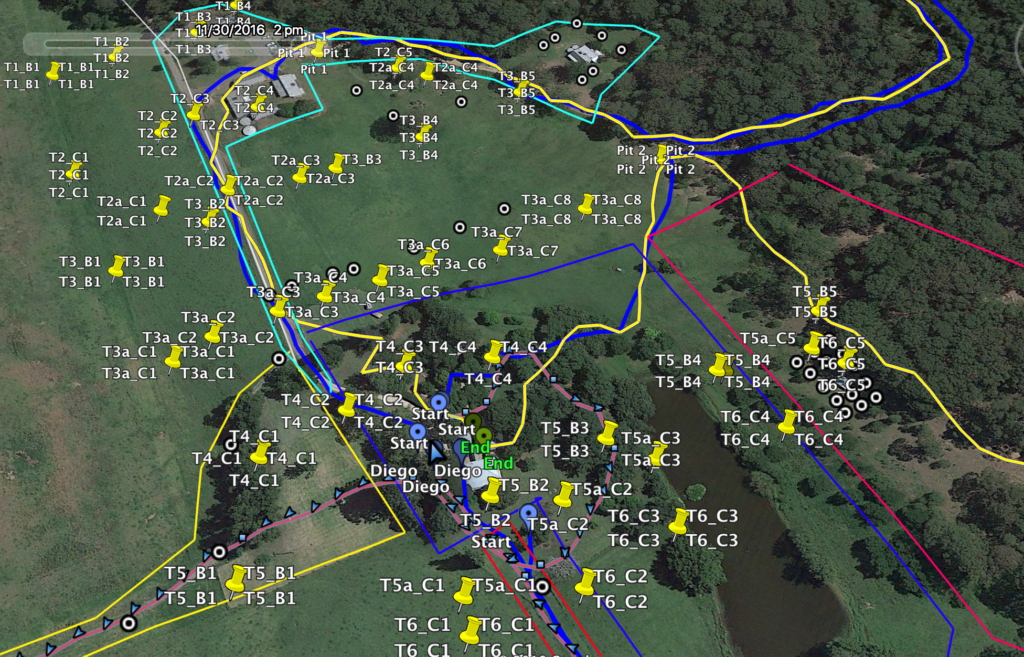

04. AudioNomad screenshot of spatial audio editing screen for the Run Silent Run Deep project, National Museum of Singapore, 2008.

Boots on the Ground.

At the beginning of the current Where Science meets Art research project a simple question was posed — How does one get under the skin of a place, of an environment?

The Bundanon Trust is located in rural New South Wales on Australia’s east coast. Its landscape comprises some three thousand acres, with many kilometres of river frontage and a topology that ranges from open pastureland, wooded ridges, rain forest gullies to human occupation sites. It is complex in the physical, biological and historical domains — so how to get to know the terrain in all of its many forms?

One of the, perhaps simple minded, solutions has been to invite ‘old hands’ to take a walk. Each person was invited to decide on a route that contained points of interest linked to a thematic — some were focussed on history, others on botany, some simply on magnificent views of the landscape, but all were intensely personal and all were different.

The residue of these walks; photographs, audio recordings and GPS tracks form a mosaic of personal knowledges, memories triggered by and situated in landscape. This process combined serendipity with very specific and nuanced information forming an idiosyncratic ecology of memories, thriving in unique landscape niches, like hitherto unidentified species! It fleshed out the bones of the landscape and rattled the skeletons of history.

05. and 06. Screenshot of soil data sample locations at the Bundanon Trust also showing walking routes – the elements found at data points are sonified and visualised for mobile devices, 2016~7.

The gradual accumulation of these individual psycho-geographies to become an archive of memories and stories that reveal the Bundanon landscape builds upon the western tradition in which knowledge is inscribed, circulates and laid in store.

However these personal journeys are but trivial fragments when compared to the complex, ancient networks of indigenous song and ritual which maintained the law and created the landscape. Traditional Song-lines situate cultural memories, knowledge and social organisation as shared narratives entwined across the landscape, or indeed which perform the landscape.

It is an unreconciled tragedy that European settler societies have been and still are, all but blind to the intangible cultures of First Nation Peoples, especially in regard to their sophisticated concepts of singing up the country — an art that perhaps many cultures, including, the ancient Europeans, may once have practiced but long ago lost.

European footsteps on this ancient land carried flags, symbols of possession in a land deemed Terra nullius. In short order flags were followed by the rational instruments of cartography, setting out a triangulation of ownership, of control and exclusion, enshrining paper boundaries that contained scant knowledge, but abundant information.

05. and 06. Screenshot of soil data sample locations at the Bundanon Trust also showing walking routes – the elements found at data points are sonified and visualised for mobile devices, 2016~7.

For millennia it was otherwise, the land owned it’s people. People who had watched as the glacial climate transmuted the oceans, the landscape and every element of the ecology. They were both spectators and participants in cataclysmic acts of creation and transformation. The land-bridges between Australia and the rest of Asia came and went, the Mega-fauna died out and forest-cover expanded or shrank according to the availability of water in the cool arid environment. People looked and remembered, the knowledge woven into the fabric of ceremony and song embedded in the landscape so that none of this was forgotten — an intangible cosmos too subtle for Europeans to fathom.

Has much really changed since first-contact? Even as the colonisers dispossessed the traditional owners of their land and their culture, the colonisers themselves became deracinated, by casting aside lineages, ancestry and cultural bonds with place, they became alienated in the very land they sought to possess.

In exploring the pervasive conditions of suburbanisation and automobilisation Rebecca Solnit focusses on the increasing disembodiment of everyday life and a concomitant sense of isolation.

Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors…disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.

By trading being for having, by the crude attachment to material culture, to speed and to a belief in incessant growth we are effectively debarred from contemplating alternative ways to understand the natural world and ways to form new relationships with it. — save perhaps for a final and certainly unfashionable thought.

Consider the options: The automobilised individual is no longer a participant in the commons; is sundered from the public vis a vis; physical movement is restricted to minor foot and hand movements, amplified into a violence of speed. The eyes gaze through a screen as a panorama slides by too fast to be taken in by indifferent eyes.

The digitised individual: An even more sedentary existence, gazing, unblinking into the shallows of a screen — into a world one photon deep populated by ersatz relationships offering only the shadowy promise of a Digital Loneliness.

An alternative is to dream for a moment — pull on Thoreau’s old leather boots and step through the door, alone or perhaps in company with Nietzsche, to walk an unknown path – walking, leaping, climbing, dancing preferably on lonely mountains. To walk and imagine a world unconstrained and unprescribed — to fall into an uncertain future but one full of potential.

And to misquote Timothy Leary’s mantra:

Turn off, Tune out and Walk on……